Transcript for Episode 3, 2023 Season Talking Hoosier History

Written by Justin Clark

Produced by Jill Weiss Simins

“This is Mr. Yuk. His green face tells children that the contents of harmless looking containers can make them very sick. Of course, potentially harmful products should be kept away from children, but if you suspect a poisoning, call the Indiana Poison Center toll free for prompt, reliable help 24 hours a day. Mr. Yuk stickers and poison information are free at all Hook’s drug stores; just ask your pharmacist in green. And pick up syrup of ipecac, the universal poison antidote at Hook’s. Together, they could save a life.”

That was veteran Indiana broadcaster Jim Gerard, the voice of Hook’s Drug Stores, promoting one of the company’s numerous public health campaigns during the 1980s. Alongside providing Mr. Yuk stickers and poison control information to customers, Hook’s sponsored a state-wide poison control initiative that, as the Nappanee Advance-News reported, “include[d] a $40,000 grant. . . to establish a statewide network of regional hospital emergency treatment centers to provide close at hand emergency treatment throughout the state.” These campaigns, focused on helping the community and keeping children safe, were among many of Hook’s public initiatives during its 90-plus years of business.

When John A. Hook started his pharmacy business in 1900, he was committed to fulfilling the medical needs of his community. As his small chain of stores expanded into a statewide and the regional brand through the decades, the company’s community commitments continued to grow. In addition to offering affordable health goods and services, Hook’s advanced racial equality and worked to prevent drug abuse, demonstrating its mission as more than just a pharmacy. While pharmaceutical companies have less trust with the public today, the history of Hook’s Drug Stores shows a markedly different trajectory—one of a community-conscious company whose stakeholders were more than just shareholders.

I’m Justin Clark, and this is Talking Hoosier History

John August Hook, the founder of Hook’s Drugs, was born on December 17, 1880, in Cincinnati, Ohio. August and Margaret Hook, his parents, were both German immigrants who came to the United States in 1869, looking for a better life. His father was a beer brewer who first made roots in Cincinnati before moving the family to Indianapolis by at least 1891. At the age of 19, John A. Hook knew exactly what his profession would be—a pharmacist. He returned to Cincinnati for his education, graduating from the Cincinnati College of Pharmacy on June 9, 1900. He earned three medals for outstanding academic work, including “a gold medal for highest general average, a gold medal for highest materia medica, and silver medal for chemistry.”

A wunderkind of pharmacological science, Hook was eager to start serving his adopted community of Indianapolis. Shortly after graduating, Hook purchased a pharmacy back in Indy known to the locals as a “Deutsche Apotheke” at 1101 South East Street. The son of German immigrants, Hook saw it as vital that he serve the German community, which had greatly expanded in the Fountain Square neighborhood of Indianapolis.

To fulfill that mission, Hook partnered with the enterprising Edward F. Roesch, who he hired in 1905 to manage a second store, to spread his business across Indianapolis. Within 30 years, they grew their drug store chain to 41 locations across Indianapolis.

One essential component of this growth was building and designing new stores, and Hook and Roesch partnered up with another legendary Indianapolis business, the architectural firm of Vonnegut, Bohn, & Mueller. Architects Kurt Vonnegut, Sr. (the father of acclaimed author Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.), Arthur Bohn, and Otto N. Mueller designed numerous drug stores for the company, either with completely new buildings or remodels of buildings that Hook’s Drugs previously purchased. Hook also used this opportunity to improve the shopping experience for customers. As an example, in 1937, Hook’s commissioned Vonnegut, Bohn, and Mueller to design a store in the Broad Ripple neighborhood. “Vonnegut, Bohn, and Mueller are the architects and have given every thought and consideration to the comfort of the customer,” wrote the Indianapolis Star, “such as soundproof ceiling, lighting, and attractive floor design.” The thriving partnership between Hook’s and the architectural firm lasted for nearly 20 years, with the latter’s innovative and attractive designs putting the customer experience above all else.

With John Hook’s death in 1943 and Edward F. Roesch’s subsequent death in a car accident, their sons August F. “Bud” Hook and Edward J. F. Roesch took over the family business, as president and vice president, respectively. Their combined leadership led to a profound expansion of the business, with a corresponding commitment to the communities they served. As the Indianapolis Star wrote, “under the joint leadership of the two men the chain grew from an Indianapolis operation to a state-wide chain of stores.” In 1958, Hook’s operated 50-plus stores throughout Indiana, employed more than 1,000 workers, and even received an award from E. R. Squibb & Sons, one of the country’s leading pharmaceutical manufacturers, for filling nine million prescriptions in its 58 years of business. Hook’s published advertisements in newspapers across the state to share their medicinal milestone. “A Confidence Repeated. . . 9 Million Times,” the splashy advertisements boasted in the pages of the Terre Haute Tribune, among others. By 1973, the company had expanded its stores to “80 communities” throughout Indianapolis and neighboring cities.

By 1982, Hook’s was one of the nation’s oldest chain drug store corporations, ranking 14th nationally in number of sales units and 19th overall in sales volume, exceeding $260 million annually. With over 260 stores in Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio (its expansion outside of Indiana a result of the merger with SupeRx in 1986), Hook’s had become one of the largest drug store chains in the Midwest by the time it celebrated its 90th year of business in 1990.

Hook’s success and the trust it engendered in communities came from an ethos defined by entrepreneurs Robert Fish and Mike McFall as “conscious capitalism.” Instead of a business caring only about returning value to their shareholders, they argue that a business should have four basic tenets: a higher purpose, commitment to stakeholders instead of shareholders, an innovative and trusting culture, and conscious leadership. Fish and McFall’s successful business, Biggby Coffee, displayed all these tenets, and for its 90-plus year history, so did Hook’s.

Hook’s higher purpose was to provide its communities with the best possible service and products that improved their lives, mentioned earlier. Its commitment to stakeholders, specifically the communities they served, was paramount. For example, in 1968, 19 Hook’s employees received awards “for their voluntary service to civic and charitable organizations.” Hook’s facilitated an innovative and trusting culture, from customer-centric buildings to providing training for its staff in drug abuse prevention. And finally, Hook’s conscious leadership. An active member of the community, company founder John A. Hook served as president of the Indianapolis Council of Boy Scouts and received the Silver Beaver award in 1939 for his service. August F. “Bud” Hook, his son and later president of Hook’s,He also served the Boy Scouts and participated in many community events, such as the Indianapolis 500 parade and the Young America Sings contest. As such, the Hook’s brand became synonymous with a dedication to community-conscious commerce.

Before we move on to our next section, we’d like to share this important message.

“Ralph Thompson has an extra $5 in his pocket today. Stella Snider will save $16 on Thursday. There’s a reason so many people are smiling this week. Their Hook’s pharmacist in green will fill their prescription with a top-quality generic drug. Generic drugs can reduce prescription costs by up to 60%. Ask Hook’s about money-saving generics for your next prescription. Because we like to see you smile!”

One significant way that Hook’s demonstrated its commitment to communities was through civil rights initiatives. In 1946, deep in the era of Jim Crow segregation, Black pharmacist and entrepreneur Murray L. Miller earned a promotion to manager of the Indiana Avenue location. As the Indianapolis Recorder wrote of his promotion, “he thus becomes the first Negro to be given responsibilities of management of this busy store . . . . Hook officials said Mr. Miller has demonstrated to their complete satisfaction his competency, ability, and efficiency, and his promotion was in line with the company’s policy of advancing employees on the basis of merit.” A year later, the firm desegregated its lunch counters at all locations, years before the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Indianapolis Recorder carried coverage of Hook Drugs’ desegregation of their lunch counters, which the Indianapolis Civil Rights Committee and the broader community fought tirelessly to achieve. As the Recorder noted, “committee members will continue going into various Hook’s stores in order to make certain that the new policy is put into practice.”

In 1965, Hook’s President Bud Hook served on a committee modeled after California’s Chamber of Commerce for Employment Opportunity. The committee’s goals were to “secure maximum employer cooperation in the employment and advancement of minority groups in the community,” “establish a 2-way communication . . . to make known employment need and opportunities,” and “assist other organizations and individuals to improve their programs for enhancing the employment of minority group or disadvantaged workers.” By 1969, Hook’s put these recommendations into practice, raising its minority management in Indianapolis to 10%. W. Howard Bell, an African American manager, implemented the innovative “Santa Claus Comes to the Ghetto” sales initiative, which gained coverage in the local press. (As an important aside, using the term “ghetto” to reference a Black neighborhood would be problematic today, but Bell’s intentions for his Black neighbors was positive.) The program was “aimed at giving customers a chance to obtain some items at reduced cost without waiting for the after-Christmas discount.” By 1972, Bell would own four drugstores of his own. Alongside management of their stores, Hook’s also promoted Black staff to corporate positions. In 1973, the firm appointed Ray Crowe, acclaimed athlete, coach, and politician, to store employment supervisor in its personnel department.

Regardless of these initiatives, the company was not without its controversies, which often appeared contradictory to its socially-conscious image. The employees of the Hook’s store in the Marwood neighborhood of Indianapolis ran a paid editorial in the Jewish Post on January 16, 1976, criticizing the company’s labor practices and its attempts to block unionization efforts. One hundred and fifty salesclerks of Hook’s “mann[ed] picket lines at many of the stores throughout Marion and Johnson Counties,” the editorial noted. It alleged that workers voted to be represented by the Retail Clerk’s Union-Local 725, and despite this vote’s certification by the local labor board, Hook’s “ignored this vote and refused to bargain” with them. It also accused Hook’s of hiring replacement labor and a public relations campaign against them. “We ask that we be treated fairly and with respect by the Hook’s Drug Company,” the editorial declared, “and that negotiations in good faith begin at once.” It is unclear whether the unionization effort was successful.

Despite these controversies, Hook’s reputation within communities remained strong, in part due to its promotion of broader public health initiatives. Starting in the late 1960s, Hook’s implemented a protected packaging program, developing a child-proof, lock-on cap and amber colored bottles that protected medicine from sunlight. Both were offered to customers at no extra charge and the company heavily advertised these services in newspapers across the state. Regarding the “lock-on safety cap,” one TV advertisement declared (audio from linked YouTube Clip): “Safety caps are specially designed to be difficult for little hands to open and to keep potentially harmful medications away from youngsters.” As for the “amber colored” bottles, another advertisement read: “This is an amber colored bottle designed to ‘lock out’ light rays that may weaken your medicine. Many drugs lose their strength when exposed to light. . . but amber glass or plastic gives prescriptions 98% protection against light. We use amber bottles and vials for every prescription . . . At no extra cost to you.” Hook’s even provided a “poison counterdose chart” that “could prevent serious injury or even save a life should accidental poisoning occur in your home.”

Alongside drug safety, Hook’s was active in drug misuse/abuse prevention and education. Pharmacists routinely spoke to community organizations and received training from the Pharmacists Against Drug Abuse Foundation and the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. As the Indianapolis Star reported, “Many Hook’s pharmacists serving in stores and in administrative positions have given countless talks to schools, churches, and other social action groups” about drug abuse and its prevention.” In 1981, Hook’s co-sponsored a 10-week “anti-drug abuse public service campaign” entitled “It Takes Guts to Say No.” Hook’s Executive Vice President Newell Hall said of the initiative, “as a corporation we are committed to providing professional prescription service to our communities and feel it is our duty to inform the public about the hazards of substance abuse.” Hook’s also provided literature to consumers about the dangers of drug abuse. In 1984, the company “published a new brochure about the symptoms of drug abuse and what parents can do if they suspect this problem exists in their families.” James M. Rogers, Hook’s vice president of public relations, told the Banner, “Our brochure offers facts and common-sense information for parents and children alike. If prevention doesn’t work, early detection is critical.” Hook’s “Parent Guide to Drug Abuse” pamphlets were available for free in all their stores.

From its advancements of civil rights, innovative packaging programs, and drug abuse and prevention initiatives, Hook’s served as a trusted community leader for decades and developed its own unique form of conscious capitalism.

The end of Hook’s Drugs came like the end of so many businesses during the 1980s and 1990s: through corporate mergers. In 1985, Hook Drugs, Inc. merged with the Ohio-based grocery chain Kroger, maintaining its brand name in Kroger stores. This merger ended in 1986, when Hook’s and the SupeRx drug store chain, both owned by Kroger, split off into their own firm, Hook-SupeRx, Inc. In 1994, Revco, a drugstore chain based out of Twinsburg, Ohio, announced its plan to buy Hook-SupeRx, Inc. for an estimated $600 million. Unfortunately, this consolidation came with job cuts and store selloffs as a way for Revco to appease federal anti-trust regulators. Less than three years later, Rhode-Island based CVS bought Revco on February 7, 1997, at a cost at $2.8 billion, and with it, gradually retired the Hook’s brand. While the legendary name is gone, many former Hook’s locations still operate today under the CVS banner.

Despite no longer being in business, the company’s legacy lives on at the Hook’s Drug Store Museum, which opened at the 1966 Indiana State Fair. Originally a three-month exhibition, it eventually became a permanent attraction. The museum recreates what a Hook’s drug store was like in the early 1900s and remains in operation today at its original location at the fairgrounds. Reflecting on its success years later, writer Judy Keene observed, “the Hook’s Historical Drugstore and Pharmacy Museum has become a national acclaimed tourist attraction. It has garnered many awards from both pharmaceutical and historical organizations, and millions of individuals have visited from every state and many foreign countries.” And in 2022, an historical marker on the history of Hook’s was dedicated near the location of John A. Hook’s first store, with members of the Hook family and former employees in attendance.

In its 90-plus years, Hook’s drugs went from one store in the Fountain Square neighborhood to one of the largest drug store chains in the United States, with over 380 locations and millions in sales. Even as it grew, the company never lost sight of its commitment to innovation, positive change, and community involvement. From its stand on civil rights to its drug abuse prevention programs, Hook’s became a brand synonymous with fairness, kindness, and the personal touch. As the collective memory of Hook’s fades, it is important to recognize its unique brand of community-conscious capitalism. Also, we must remember its motto from years ago, words that rang through its many ads and embodied its ethos— “We like to see you smile!”

“We like to see you smile, that feeling good feeling, that smile on your face, there’s a lighter kind of place. Hook’s likes to see you smile. Hook’s is the name you trust, and we won’t stop trying to give you our best. Hook’s likes to see you smile; we like to see you smile!”

To learn more about Hook’s Drug Stores, check out my article, “We Like to See You Smile: The Story of Hook’s Drug Stores” on our blog. A link will be in the show notes.

This episode was written by me, Justin Clark, and produced by Jill Weiss Simins. Find a transcript and show notes for this and all our episodes at podcast.history.in.gov. And remember to subscribe, rate, and review Talking Hoosier History wherever you get your podcasts. Thanks for listening!

Show Notes

Produced by Jill Weiss Simins. Written and performed by Justin Clark. Research and editing support from Dr. Michella Marino.

This episode is based on the article “We Like to See You Smile: The Story of Hook’s Drug Stores,” by Justin Clark. It is available on the Indiana History Blog where you can also find notes and sources, along with images.

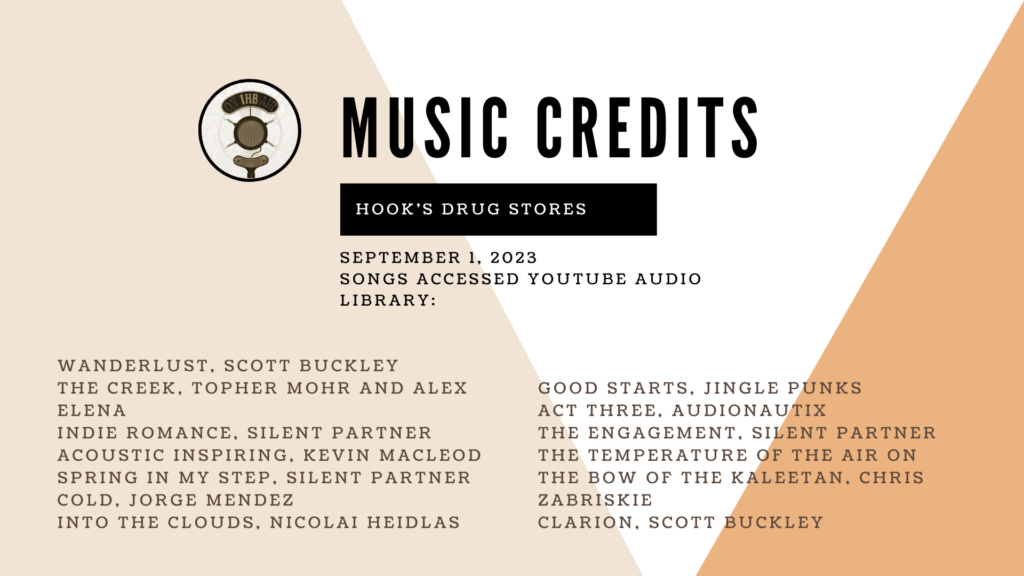

Music Credits