Transcript for Episode 5 of the 2023 Season of Talking Hoosier History

Written by Dr. Michella Marino. Produced by Jill Weiss Simins.

Attendees at the Gay Pride event on Monument Circle could feel the tension in the air. On one side, queer Hoosiers, who felt proud to be publicly celebrating their sexuality, gathered to exercise their constitutional right to assemble, promote gay civil rights, and foster community. On the other side, conservative Christian Hoosiers, who felt their religious beliefs were threatened by the event, demonstrated their disapproval of what they viewed as sinful lifestyles. The Pride attendees could certainly hear the hostility as protestors hurled offensive words their way, trying to intimidate queer Hoosiers back into their closets. The Indianapolis Men’s Chorus, a newly formed choir composed of talented gay singers focused on fellowship, was slated to kick off the Pride event. They were slowly making their way up the steps towards Lady Victory as the chaos reached a crescendo around them. Just as the choral director, Michael Hayden, and the singers assembled, dozens of protestors wielding baseball bats, stormed the stage, armed with “an attitude of confrontation.” Unsettled onlookers felt helpless to stop what was surely heading for a contentious, and perhaps even bloody, confrontation.

I’m Justin Clark, and this is Talking Hoosier History.

The aforementioned Pride event dubbed “Celebration on the Circle,” was held at Monument Circle on Saturday June 29, 1991. The Indianapolis gay community had been venturing further out into public spaces during the 1980s and early 1990s. Yet, it was still dangerous to live openly as a gay man or lesbian in the Midwest. The vibrant gay bar scene and city activists were working on changing that by the early 1990s, but it was a long fight and is one that continues across the state of Indiana.

One important development, among many, of Indianapolis becoming a more welcoming city to LGBTQ folks was the founding and then performances of the Indianapolis Men’s Chorus. The Men’s Chorus was founded by the non-profit Crossroads Performing Arts, Inc. Crossroads, whose steering committee was originally under the direction of Jim Luce, had been working since January 1990 to lay the groundwork for the Men’s Chorus with future goals to establish a Women’s Chorus and an instrumental group. Recruitment for the Men’s Chorus began by the end of March 1990, and the founding choral director, Michael Hayden, who was also a music professor at Butler University, was hired in August that year. Vocal auditions were held in late September and early October, and the Men’s Chorus began practicing on October 14. The group planned to formally debut in spring 1991, which they did at the historic Madame Walker Theater on Saturday June 8.

Crossroads’ mission was to “strengthen the spirit of pride within the gay/lesbian community, to build bridges of understanding with all people of Indiana, and to enable its audiences and the general public to perceive the gay/lesbian community and its members in a positive way.” It is not surprising then, that the newly formed Men’s Chorus was slated to perform at the Gay Pride celebration in Indianapolis in late June 1991, as part of their debut season. This was only the second Gay Pride event held at Monument Circle. Pride events, hosted by various organizations such as Justice, Inc., had been held in the city in the past, but throughout the 1980s they were semi-closeted, meaning they were held in a hotel, bar, or rented space that was not actually out in the public—it was deemed too dangerous to be that open. In 1988, however, the Pride celebration expanded with a festival held at the more public Indianapolis Sports Center. Approximately 175 people showed up, and by the very next year, when the event moved to Westlake Park, the attendance numbers had dramatically risen to 1,000.

Yet, the gay community still had real cause for concern, particularly as its members began celebrating more openly and in highly visible spaces. In 1990, the Pride festivities continued to expand and moved to Monument Circle for the “Celebration on the Circle.” Virulent anti-gay protesters from a variety of Indianapolis churches wanted to intimidate them and showed up with their “fundamentalist anger.” According to the Indianapolis Star, approximately 100 protesters were on the scene, “many of whom wore gas masks and shouted insults as they walked around Monument Circle.” One anti-gay demonstrator explained why they were at the Circle: “We are all Christians who are here because we don’t approve of what these people are doing, trying to turn Indianapolis into another gay capital like San Francisco…I find it objectionable that they want to take their unholy, unacceptable lifestyle to the center of the city.”

The second Pride event at the Circle was noticeably more hostile. First off, in April 1991, city officials denied Justice, Inc. permission to hold the Pride rally at Monument Circle, citing a temporary policy limiting “traffic disruption and police overtime as the reasons.” The Indiana Civil Liberties Union (now the ACLU of Indiana) quickly planned to challenge the decision in court. Within weeks, Safety Director Joseph J. Shelton relented, stating, “The thing that really changed my mind about it is the fact that regardless of what we say or what we do, the outright appearance was that we were only imposing this restriction on this group… just because of the gay and lesbian organization.” After organizers obtained the green light to host their event at the Circle, Pride attendees, including the Men’s Chorus singers, were still not exactly sure how they would be received by their own city and its citizens.

Hayden recalled having conversations with the singers about whether they wanted to perform at the Pride event and how the chorus would be sensitive to its members’ differing levels of comfort. They were right to have concerns. Religious protesters, angrier than at last year’s events, were in the mood for blood. And they arrived with baseball bats. Jim Luce wryly observed, “Because Jesus would have a baseball bat, right?”

Taking a quick break from our story here, we just want to pause to say, studying queer history is hard, at least in terms of sources. For much of American history, LGBTQ Americans, were considered “illegal” or at the very least ostracized, and thus were never encouraged to live openly and share their stories, much less leave a paper trail detailing what their lives were like. This slowly changed in the mid-twentieth century, when gay individuals began connecting informally and formed organizations that fostered community and often promoted their rights. They became the keepers of their own history, even if they could not share it widely until much later.

However, in recent decades, repositories across the country and in Indiana have begun focusing on gay history and the collections of activist groups. For instance, the Chris Gonzalez LGBT Archive Collection is held at the Indianapolis Public Library and has been digitized by IUPUI. The Indianapolis Men’s Chorus/Crossroads Performing Arts, Inc. records—which were consulted for this podcast—are housed at the Indiana Historical Society. In particular, we want to highlight a collection new to the Indiana State Library, which “comprises the records and collections of the Northeast Indiana Diversity Library (NIDL) from Fort Wayne, Indiana.” NIDL was a “non-profit organization that served the local LGBTQ community, documented its history, and collected books, periodicals, pamphlets, manuscript collections, ephemera, and other items relating to the queer experience. The dates for the materials range from 1919 to 2023” and highlight the history of Gay Hoosiers outside of Indianapolis, broadening our understanding of Indiana’s queer history. This rich and diverse collection, part of which is digitized, has been fully processed and available to the public for research through the State Library’s Rare Books and Manuscripts department.

Jumping back to the opening segment of our podcast, Hayden and the Men’s Chorus, including Luce, walked right into the hostile scene. As the 1991 Gay Pride event was getting ready to kick-off, approximately 40 protesters stormed the stage. Lt. Tom Bruno, of the Indianapolis Police Department’s traffic unit, described the protesters as being armed with “an attitude of confrontation.” As tensions mounted, John Aleshire, a spectator at the event who later went on to chair the board of Crossroads Performing Arts, was disturbed by what was taking place before his eyes. He was both fearful of what was to come and felt helpless to stop it.

But right as the fundamentalist protesters and rally attendees, including the Men’s Chorus seemed ready to clash, Michael Hayden, the choral director, made a split-second decision that altered the course of events. He had the foresight to choose the only song that could defuse the tension and make the bat-wielding patriot Christians stop in their tracks. He looked at his men and said, “Sing the national anthem. Right now.” Pride attendees encircled the unwelcome protesters on the stage and assailed them with music. According to the Indianapolis Star, “it was a tense moment,” but as Aleshire recalled, “something magical happened.”

As the Men’s Chorus members armed themselves with their voices, the protesters were taken aback. Luce described the scene: “It was fascinating to watch that group of people actively hating us while we were singing the National Anthem. I mean they actively hated us.” One onlooker later wrote, “Those who had wrapped their religion in Old Glory were hearing those ‘sissies’, ‘faggots’, and ‘moral degenerates’ demonstrating that the ugly protesters held no monopoly when it came to expressing their love of country.” And as Hayden queried, “What could they say? How could they protest America’s national anthem? There’s no way.”

In recent years, our national anthem has been at the center of controversy in terms of its meaning and our reactions to it. The anthem is, for some, a sacrosanct representation of America and to question it, to kneel during it, has become an act of such disrespect as to dominate national dialogue. But clearly questions have emerged, and indeed remain, regarding the idea of ownership and interpretation of the anthem. Does the anthem belong to all Americans and represent us as a cohesive national unit? Or do individuals have the ability to display their patriotism in their own way? Essentially, who gets to embody the American identity, and who gets to invoke their rights of citizenship, like the ability to gather in public? Who gets to make the decision about how we, collectively and individually, display our patriotism or call our country to be its best self and live up to its own ideals? To whom does our national anthem belong?

Hayden, in that moment, understood what was at stake for queer Hoosiers during the conflict on Monument Circle: not only their right to be out in public as gay men and women, but their very Americanism. Hayden recalled thinking, “We’re Americans too. Shut up. We’re going to own this just like you. That flag represents us as well.” The fundamentalists faced a choice as the notes of the “Star Spangled Banner” assailed them: put their hands over their hearts as they had been taught that all loyal Americans should do when they hear our national anthem or charge full-force ahead at another group of patriotic Americans, nee Hoosiers, invoking their right to celebrate in a public space. The protesters ultimately stopped and paid their respects to the anthem, which created just enough pause to dull the escalating tension. In Hayden’s words, “We had sung them off the monument steps.”

After the protesters exited the stage, events were able to carry on without further disruption. No arrests were made, and no violence occurred. Attendees were proud of how the Pride event transpired, but fear of being so openly exposed continued to permeate throughout the day. Activists, particularly those with ties to the Men’s Chorus, remember with pride how they sang down the hatred using their own patriotism. Hayden described the Men’s Chorus singers as being these relatively young “homegrown” men, Hoosiers in their 20s and 30s who were “from these great families from Indiana.” And after the situation was defused, they started cheering and hugging each other, and processing what they had just done. The following month, Hayden wrote to his chorus to reflect on their experiences: “Seeing a man carry a ball bat or standing on the steps with them shouting in our faces just trying to enlist us to violence … and then this mighty male instrument opening its mouth and singing these ‘Christians’ right off the steps! Goliath has never seen a stronger David. I have never felt so proud to be gay, a musician, and what we know to be a true Christian in my entire life.”

Decades later, Hayden could still recall the emotions, power, and importance of what transpired that summer day. He reminisced, “We all felt it, and we knew we had done that with our voices and our national anthem.” Aleshire confirmed these feelings, “It proved to me, once again, that music is one of the most powerful forces to bring down walls and build bridges in their stead.”

To learn more about the 1991 Gay Pride event at Monument Circle, check out Dr. Michella Marino’s piece “‘We Had Sung Them Off the Monument Steps:’ Pride, Protest, and Patriotism in Indianapolis,” on IHB’s blog. A link will be in the show notes. Markers are also a great way to learn about Indiana history. Check out our state historical marker on the Origins of Indiana Pride installed in 2021 at…you guessed it, Monument Circle in downtown Indianapolis, where the 1990 and 1991 Celebrations on the Circle took place. The marker highlights how these early Pride events provided “public space for attendees to socialize, learn about their rights, and hear from AIDS activists. Despite the presence of protestors, the event empowered attendees, challenged social stigmas, and welcomed a range of sexual and gender expressions,” all in the “land of the free and the home of the brave.”

This episode was written by Dr. Michella Marino and produced by Jill Weiss Simins. The archival audio clips used in this episode are from a 2018 IHB oral history interview with Michael Hayden and from the 2014 Indianapolis Men’s Chorus Documentary, “Yesterday, Today, & Tomorrow,” available via YouTube. Find a transcript and show notes for this and all our episodes at podcast.history.in.gov. And remember to subscribe, rate, and review Talking Hoosier History wherever you get your podcasts. Thanks for listening!

Show Notes:

Written by Dr. Michella Marino and performed by Justin Clark. Produced by Jill Weiss Simins.

Notes and sources: https://blog.history.in.gov/we-had-sung-them-off-the-monument-steps-pride-protest-and-patriotism-in-indianapolis/.

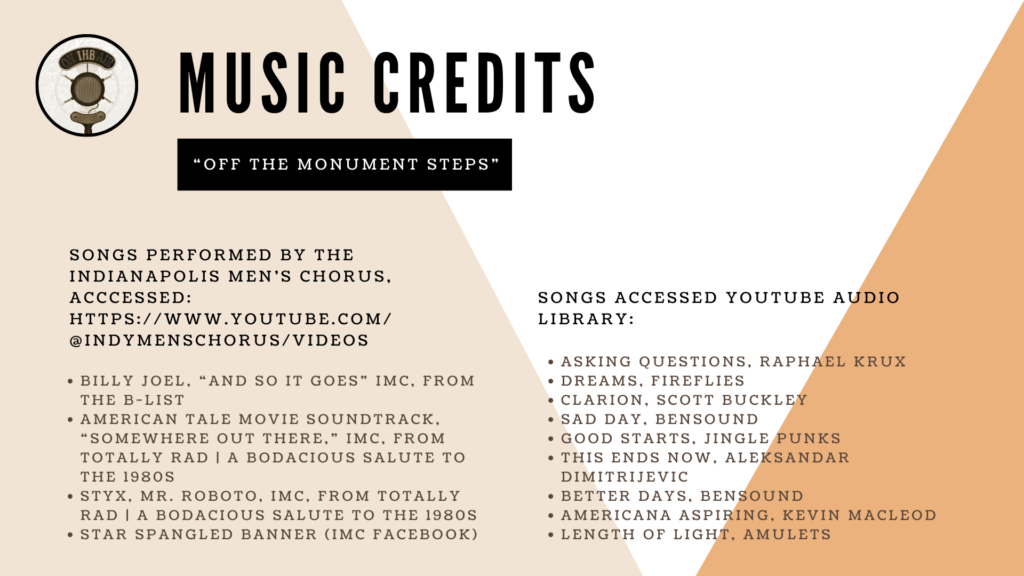

Music Credits: